A certain amount of stretched heartstrings was inevitable with viewing Miyazaki’s ‘Farewell Masterpiece’, but even major fans of his work will find themselves ill prepared for what they are getting into. The Wind Rises isn’t just Miyazaki’s farewell masterpiece but simply his best movie. Ever.

Although Miyazaki is generally known as a children’s fantasist in anime style, his work has always had an amazing range, from the lighthearted fairy tale of Ponyo to the morally ambiguous and yet profoundly mythic Princess Mononoke. That’s not to say that even his light fare such as My Neighbor Totoro doesn’t have its amount of darkness and his darker fare such as Spirited Away its playful whimsy. Its his ability to balance and give consideration to all aspects of his storytelling that makes him a master storyteller. Miyazaki has always had a strong ability to guide viewers through honest and appreciative stories that sought the good in his own characters.

Which is why it feels weird to say that The Wind Rises is Miyazaki to the extreme. It seems like a contradiction in terms but is entirely accurate. In The Wind Rises, he manages to make a movie more beautiful to watch and more enchanting to experience… and more troubling to think about and more heartfully traumatic… than anything else he’s ever done. He even pushes his visual style to the limit.

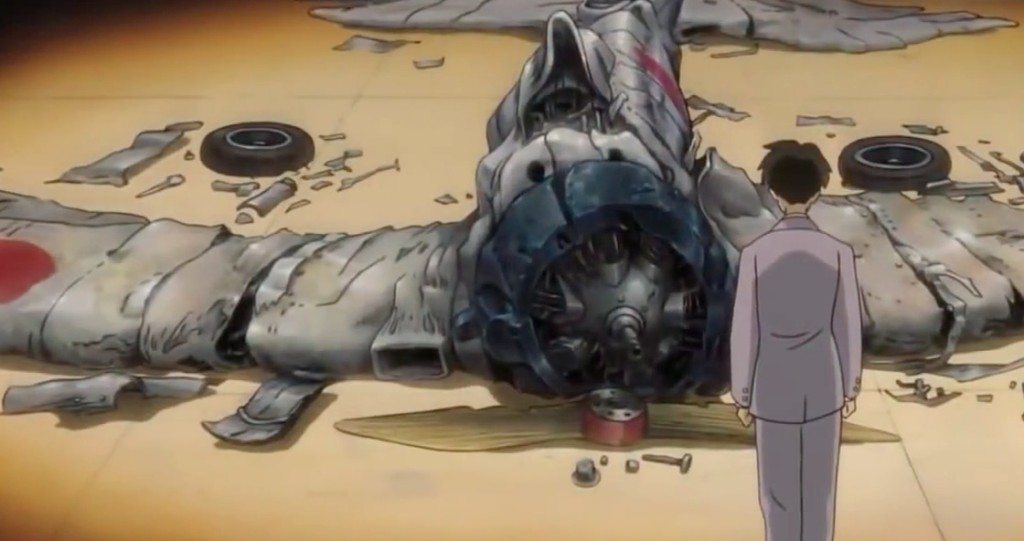

The story is drawn from two sources, both equally heavy. The primary focus is Jiro Horikoshi, real life Mitsubishi engineer in the years leading up to World War II. The story starts with Jiro as a young boy, who meets famed aeronautical engineer Giovanni Caproni in a dream. The whimsical Italian shows Jiro his new design and encourages Jiro’s desire to become a designer, with the warning that planes are meant for flight, not money or war. Upon waking, Jiro’s path is realized and he sets himself immediately to work, studying harder than his fellow students and quickly gaining attention amongst the industry for his knowledge and drafting skills, until he becomes head engineer on a new project of which history buffs will know the outcome.

The second source is Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, a novel about two lovers, one ill, on a mountain retreat. This source is cited directly by characters within the movie and quotations from Mann employed in the dialog. On his way to Tokyo University, Jiro meets a young woman named Nahoko Satomi, and their lives are thrown together as an earthquake derails their train. Their paths cross again on a mountain retreat, their blossoming romance overseen by Nahoko’s father and a cheery German, in Mann fashion of which literary buffs will know the outcome.

If you are neither a history buff nor a literary buff, don’t worry. You’ll still be clear about the outcome. Jiro the character designed by Miyazaki has an almost preternatural sense of causality, in a manner graphically represented by his slipping in and out between day-to-day work and dreams. His dreams themselves always seem to be of two parts, an initial thrilling, zero-gravity flight amongst the clouds, followed by bursts of flame and smoke and crumbled, blackened planes. Despite setbacks and accidents both real and imagined, and the foreboding effects of Japanese and world politics around him, Jiro is driven by his love of work and Nohoko, sometimes in equal measure, seeking beauty in design and willing to pull influence from the natural places and things around him.

Jiro’s mindset is reflected in the movie’s astounding visual style. Miyazaki has pulled together the minutia of historical detail; he delights not only in the planes from the perspective of Jiro, but also designs and fashions from the era. He plays with optical trick in his possession (as well as an eye for optical distortions and illusions), causing the whole movie to feel dizzying and cerebral. And he places in full view deeply unsettling images of Japan in despair and disrepair, calling forth images of earthquakes and war and not necessarily showing natural or man-made disaster as two separate phenomena. All of this set against a Japan in economic recession, struggling to gain a foothold even as they recognize that they’re twenty years behind the Germans.

It’s worth at this point acknowledging that there are elements of this movie that are going to affect a Japanese audience much more profoundly than an American, or international, one. The Wind Rises seems like a cheery enough title, until you think about The Land of the Rising Sun. And the various images of devastation are not only sourced out of a major national trauma in history, but an existential dread that island has always suffered over the next earthquake or similar natural disaster.

And yet. The Wind Rises still manages to be a celebration of imagination and art. Jiro’s passion is infectious; his and many side characters’ love for airplanes, design, technology, and engineering is honest and intoxicating. It’s no surprise that Caproni’s early warning to a young Jiro is hardly recalled to Jiro’s mind after. The work he does fulfills him, Miyazaki celebrates it, and the audience can’t help but be infected by that enthusiasm.

Thus, Miyazaki passes the torch, and to no one in particular. Rather, he leaves the power of imagination and design to those who will be taken by it, with the prerequisite warning: it’s not for money or for war.

Miyazaki’s oeuvre as a whole has a tendency to make a person want to go running and dancing in a field. This movie ends in such a field, and the field is empty. The audience is left with a decision to either accept the emptiness of the field, or regret it. And Miyazaki makes a good argument for accepting it. It’s a very strange, somewhat perturbing, and yet powerfully seductive.

He’s not necessarily gone – apparently his retirement from film directing just means he’s going to be putting more work into drawing manga – but he’s making the outcome as clear as he can be. It’s difficult to imagine closing out with a more definitive final note.