The Omladinsko Pozoriste, in Tuzla, Bosnia, was a two-story building with a big tree in front of it. The second floor housed a music school, where the national and city choirs got together to perform and rehearse, and a music space for rock concerts. A theatre was on the first floor. It was a huge room, with blue curtains that divided the stage.

It was there, in that performing arts center, that Daniela Dakich felt safe and free to be herself. Or, as much of “yourself” as you can be as a 3-year-old, when she started going there. A shy girl by nature, she blossomed under the guidance of her acting teacher, Tomislav Krstic. He was supportive, fun, gentle and kind – traits that her father wasn’t always.

Hundreds of kids would sign up to attend the classes there each year, Daniela says, but only one or two people from each group would stick around and sign up for the following year. The teachers were professional actors themselves. Under their guidance, play-acting wasn’t all playtime.

“They would throw out all these exercises, Stanislavski-based,” Daniela says. “You had to work. Our teachers made us work hard for it.”

Just because you were in the program didn’t mean you’d be cast in one of the shows. It took three years for Daniela to grow her confidence and prove her work ethic to be cast, and her first role was way less than a lead. She played “Squeaky Door” – like, a door that was noisy – and she was thrilled about it.

“I used to watch all these Looney Tunes movies when I was a kid,” Daniela says, “so for me, it was like ‘Oh my God, awesome! I get to make all these sounds!’”

Daniela and her sister spent countless hours there in the theatre, training year-round, every Saturday and Sunday, for more than 10 years. Then, one day she left after a tiny, maybe uneventful day’s work was done, and she never went back.

War broke out between the Serbian Army and an army of Bosnian Muslim Nationals in Tuzla, while she and her family were 50 miles away at an unrelated family funeral. She watched it unfold on TV from her aunt’s house.

“We were really lucky,” she says. “We would’ve been there, and we probably would be dead.”

In a blink, that chapter of her life was suddenly closed. Blue curtains, drawn. It was all gone: the grey room, her theatre friends, the connection with the acting teacher that reminded her of her sweet grandfather. Her home-away-from-home, and not to mention her real, actual home that was across the street from the theatre.

“You can’t go back. My clothes, everything was there. My parents’ money, savings. Everything was there. You can’t go back. There is no place to go back to. There is no road to go back. People are fighting. All these armies are fighting. If you get caught, you get killed.”

She was 15 years old. She was a recent television star, having been cast two years before on an independent state network’s sketch and educational show for teenagers. Now, she and her family were refugees. As in: forced to leave their home to escape war.

They stayed at her aunt’s house on the border of Bosnia for 10 days, and then went to Belgrade, where they had some family. They were there for a month, and her mom got a job in south Serbia, where they settled (however much you can “settle” in a refugee camp), and she completed her four years of high school.

Still, acting.

“For some reason, it just kept me feeling like there’s hope. It would be some crazy stories of people doing some heroic things and surviving, and there would always be a happy ending and hope. So that kept me going. If I didn’t have that, I would have probably killed myself.”

She went back to Belgrade for law school. Still, refugee camp. Still, dreaming herself into a new life through her art and her work. At the age of 26, it was finally time to go home. Not to Tuzla. To New York City.

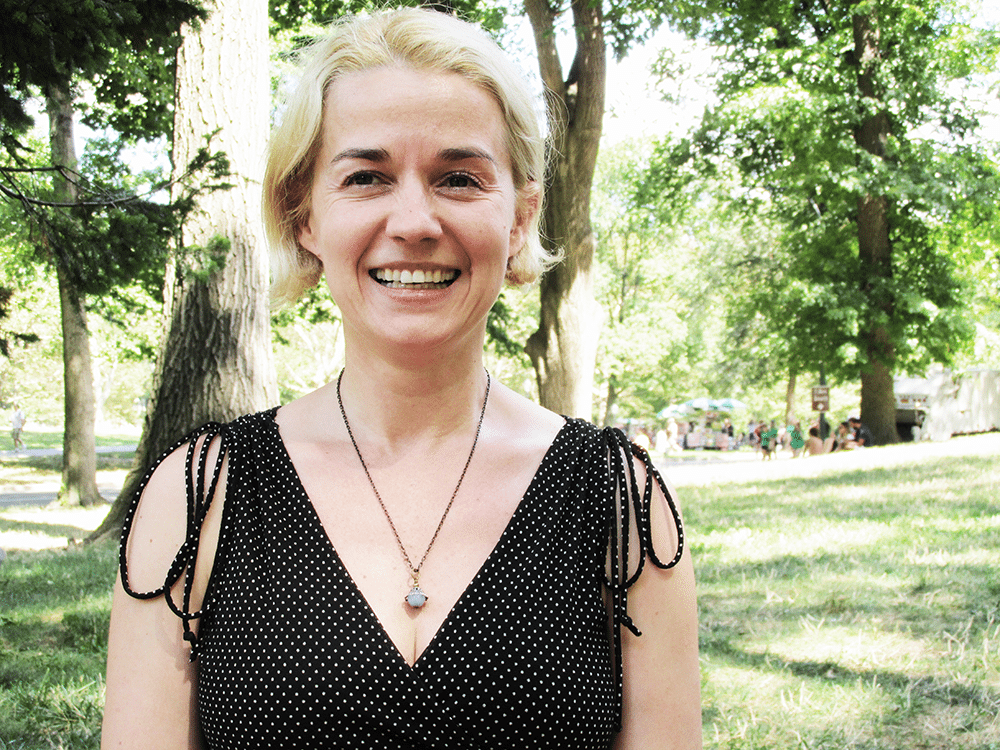

“I always wanted to come here,” Daniela says, dressed in a black and white polka dot dress, as blond and as fresh as a Misfits-era Marilyn Monroe, sitting on a blanket near the Columbus Circle entrance of Central Park. “I always felt like this is my home. Like ‘No, I don’t belong to Europe.’ I had a feeling like I belong to a different continent. You know, when you love the culture? This is the culture I like. These are the people I like. Nothing glamorous; it’s down to earth. Like really simple, down to earth. It’s all about work.”

It’s here that Daniela continues to pursue her craft in shows and showcases and with classes and ensemble work. She’s been through war, so she’s more than willing to stare down a casting director who’s looking for a reason to say no.

“It’s the really basic stuff. It’s not about, ‘Hey, am I good’ or ‘Can I do it?’ because I know I can. I’ve done it, and I’m doing it. I take classes, and I work on myself. It’s always the judgment: ‘How old are you? Where are you from? You still have an accent.’ It’s small, petty stuff. People get petty because they can.”

Daniela Dakich has been through war, so she’s not afraid of getting up at 4AM to get into a line for non-union actors who will possibly be seen by a casting director, when the possibility exists that she’ll still be waiting in that line 12 hours later. When the possibility exists that her work ethic, talent and discipline will be challenged, if she is seen, because of her accent.

“Southerners, Texans, actors from Minnesota, they all have accents, too,” she says. “But no one would doubt their talent or work ethic because their accents are familiar, from the States.”

She has more than 1000 performances under her belt from a lifetime of work. And, an agent. And she has friends, made during all that waiting-in-line time. They help each other out, sharing tips and spreading intel from casting sessions across the city.

It’s devotion to her calling and her craft, and it’s already given her way more than wild success or creative control or financial independence (things that still remain a heartbeat away) could ever hope to promise. She is in service, not to bright lights and accolades, but to one shining aspect of her craft that she credits with bringing her through the tough times in her life: hope.

“Acting felt like a place where I can be seen, and not afraid, and not going crazy. I don’t want people to think of acting as therapy, but when you live through crazy, shitty times and people are dying, and there’s no electricity or water or money or no food, you need to find something to keep you going, to make you feel better. Like there is some kind of hope. And acting is that for me.”

“Acting felt like a place where I can be seen, and not afraid, and not going crazy. I don’t want people to think of acting as therapy, but when you live through crazy, shitty times and people are dying, and there’s no electricity or water or money or no food, you need to find something to keep you going, to make you feel better. Like there is some kind of hope. And acting is that for me.”

Like this profile? Check out Seeing Red & Manwhores Need Love, Too. Got someone Kyle should interview? Let him know! [email protected] or @KyleCollins on Twitter.