The trailer for the new Coen brothers movie was a surprisingly dry tease. With stilted, almost Mumblecore dialog in desaturated imagery over Bob Dylan’s folk chords, the trailer sold the movie as any other 20-something inspired indie flick. To frustrate the viewer further, it cuts to black before the audience even hears Llewyn’s first acoustic strum. Upon unwrapping, however, Inside Llewyn Davis proves to be a box stuffed full of the Coen brothers’ best working habits, complete with amusingly dysfunctional failures of characters, dialog that variously nips and bites, and for what it’s worth, the best folk soundtrack for a movie seen since… well, the Coen brothers’ other folk-inspired Odyssey, O Brother, Where Art Thou?

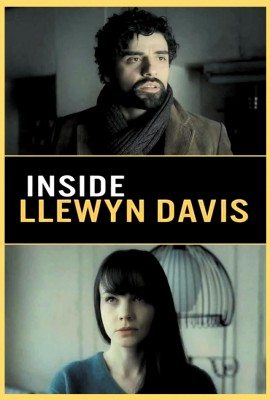

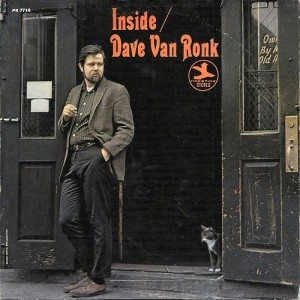

Oscar Isaac takes up the role of a couch-surfing New York folk singer in 1961, who is also a physical amalgamation of early Bob Dylan and his colleague Dave Van Ronk (the latter comparison is revealed explicitly by the cover of Llewyn’s new solo album Inside Llewyn Davis, which remakes the cover of real life album Inside by Dave Van Ronk). The movie begins in media res with an answer to the cutaway of the trailer, by settling right in to a concert at The Gaslight in Greenwich Village (again, Van Ronk’s old haunting grounds). After a pleasant introductory song you get used to the smoky enchantment of the place, rendered by new(ish) Coen brother collaborator Bruno Delbonnel (Roger Deakins was busy shooting Skyfall, so the brothers hired the director of photography from their Paris, je t’aime short). Once the piece is over, however, events quickly turn brutal, as Llewyn apologizes for hitherto unknown drunken actions of the night before to his barkeep friend, and then gets kicked and beaten outside the bar.

It turns out that the beginning is a bookend device and the background to these events are strung out from there. Llewyn Davis is feckless at best: sleeping in an unending circle of his friends’ couches, dropping his equipment off hither tither, and trying to run away from either some crushing responsibility or inner demons, it only becomes clear later which. He’s the existential and dramatic counterpoint to a slapstick hero, his thoughts always one step behind his own actions, resulting in a cascade of negative consequences.

Within the first couple of scenes he loses his upscale professor friend’s cat and is chewed out by Jean (Carey Mulligan), girlfriend of Jim (Justin Timberlake) for possibly getting her pregnant. Situations never really settle from there. As Llewyn Davis traverses the lonely New York City landscape, staving off fatigue and rolling over his debt against time into higher interest rates, we get further insight into the nature of his base circumstances. It turns out that he’s being left behind as Jean’s and Jim’s careers start to blossom, the folk scene starts to crystallize, and Llewyn has to make a decision between finding work and dedicating himself to his art. Thus the odyssey starts, as Llewyn seeks a way to get cash from his agent, the cat back to the Gorfeins, and the attention of record executive Bud Grossman, not to mention come to terms with his defiantly hidden feelings for Jean. This journey will bounce him up and down Manhattan’s west sides and between New York and Chicago, while running him into a variety of Coenish characters such as John Goodman’s appearance as a batty and overweight jazz musician.

As a central character, Llewyn can sometimes be difficult to stomach. With an abrasive personality, caustic attitude, and a constantly burning frustration, he’s every deadbeat mooch you’ve ever been friends with, except slightly more parasitic. Nevertheless the Coens actually manage to not only provoke sympathy, but actually all out empathy for his character. For all his screw-ups he doesn’t have much of a choice, and ultimately his inner motivations come down to things and people he’s lost well before the movie started. The trip he takes doesn’t operate quite like a Hero’s Journey, but rather is the medium through which we gain insight into his past. Thus the movie elegantly lives up to its name.

Whether audiences will muster it will be a different question. Inside Llewyn Davis is inverse O Brother, Where Art Thou?. Where the latter is colorful and fun the former is drab and so dry it crackles. Where the O Brother sold its soundtrack, the soundtrack sells Llewyn Davis. And rather than adapting The Odyssey with folk music, Llewyn Davis structures folk music history around an odyssey. The result is the exact type of movie that excites critics but depresses audiences.