Socially oriented themes are vital in keeping today’s art community from obsolescence. Desensitized by post-modern theory, many of today’s artists subscribe to the idea that personal narratives are as equally worthy as history’s. Often, the individual opinions, quirks and tastes of the artist trump objective social matters and form the impulse and focus of the work. As art schools and the needs of the marketplace teach the same, the common issues and conditions faced by large sections of the population go untouched as worthy subject matter in the artistic arena. This is a 21st century concern.

Artists such as Caravaggio, who worked in service of the Church at first, worked to interpret daily life. His practice of picking up street urchins and prostitutes and using them to create portraits of religious figures offered an edgy commentary on hypocrisy in the religious community. His portraits, rendered in murky chiaroscuro, asked us about the validity of the Church’s claims to moral authority. Without question, we need more artists that consciously choose to interpret and comment on their surroundings and the political goings-on of everyday life.

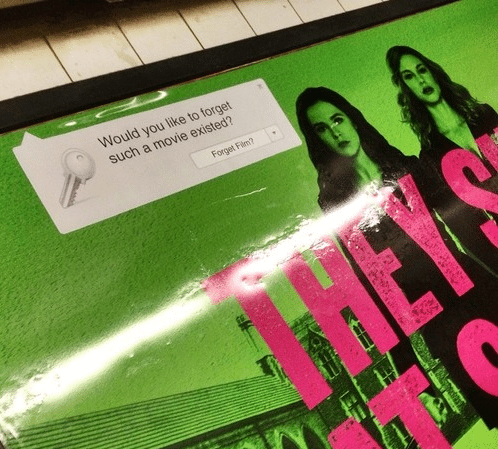

The Brooklyn-based artist known as Jilly Ballistic chooses to use the advertising seen in New York City as canvas. Ballistic augments subway adverts and movie posters with unique, one-off photo cutouts that comment and question the ad’s initial purpose. By displacing the reason behind the production of a given piece of advertising, she creates her own intent – to question the ad and engage in dialogue with the potential consumer.

A poster for a reality TV show about wealthy Southerners inserts black and white cutouts of Confederate soldiers next to the modern-day socialites; a glass-enclosed subway map is taped up with a fictional police advisory: “if it ain’t broke, break it”; a Sports Illustrated ad featuring an attractive model in bikini is amplified with the sticker “Beauty has been modified from its original version.”

One of my favorite subvertisements is Ballistic’s Would you like to forget this movie ever existed? The question is posed in a pop-up icon on the movie poster for Vampire Academy. You don’t have to dislike the movie to connect with the work. There is an ongoing critique of warfare that runs through the majority of Jilly’s interventions. Cutout soldiers and gas masks are key images that keep popping up in her work. If you catch either of these, you know it’s a Jilly Bomb.

I was able to ask Jilly several questions about her work.

Where were you born?

Born and raised in New York City.

How has NYC influenced your art?

Every piece I put up is inspired by the City, from its architecture to the ads in the subway. They are all site-specific and have a relationship with the environment, a purpose.

What recent changes in the city have affected your creative process?

My process hasn’t been affected in any negative way. Despite the huge influx of cameras and the unjustified number of stop-and-frisks, the work still gets up. You develop a strategy for things like this and adapt. For example, you alter what paste you carry and what containers; can the print go up all in one large piece or in sections? Actually, the number of obstacles makes the process more challenging and even fun to work around.

Many artists shy away from being political in their work for fear of being “on the nose” or appearing sincere. What are your thoughts on the matter?

You have a right to express or not express your thoughts on any topic. For myself, I’ll approach a political issue or respond to something in our pop culture if the time and location is right. Like I said, all my pieces are inspired by/site-specific, so if the City offers me an opportunity I take it and try to say something meaningful, either in a subtle way or with humor.

By playing with advertising, your pieces subvert the commercial. What is your overall relationship with commerce in NYC?

You can’t escape capitalism in New York. Even if you’re not actively purchasing anything, you’re exposed to the advertisements–they’re next to you in the train car, they’re on your building. We’re all in a relationship with commerce. And I use that as a common denominator; I attempt to say what the public is thinking about a product, be it a new film or Apple product.

What is a less obvious risk of creating street art?

With all the effort you put into a piece, there’s a chance the public puts little effort into understanding it.

The ‘would you like to forget such a film existed?’ piece plays with the public’s expectations of interactivity and being positioned as tastemakers. On one level it critiques media of questionable value (a cheesy, senseless teen movie) while using interactivity to offer the viewer the option to disregard content. What are your feelings on ‘tastemaker culture’ such as the foodie movement and its relationship to city life? Where do you position your art in the consumer/tastemaker culture?

Technology has changed the way we interact with the world around us, specifically allowing us the ability to talk back instantly with submitting comments, “liking,” or “disregarding.” It’s made each of us individual critics, or a “tastemaker” as you put it. This is another one of those common denominators I work with; most of us recognize alerts or error messages because they’re in our lives everyday. It has become a form of communication and a medium artists can use.

Your pieces use existing advertising and material as jumping off points. Do you have a “dream ad” or physical space that you’d love to Jilly-bomb?

One of the best parts of doing ad or site interventions is that moment when you’re commuting as you usually do, and the train passes an ad/space you know you have to hit. It’s a gut feeling, an instinct. So I don’t usually sit and dream about spaces, I let the world surprise me.

What is your opinion on a hacking group such as Wikileaks? To you, what is the relationship between art and hacking?

When mainstream media and journalists no longer take risks to uncover what’s truly happening, we have to depend on ourselves. There’s a creative way to do this-like with cinema, graffiti, or visual arts for example-or direct reporting, like revealing official documents.

Social and historical icons figure largely in your pieces. What else do you draw your inspiration from? What does the gas mask mean to you?

2014 marks the hundredth anniversary of chemical warfare and the gas mask has/is currently undergoing an evolution. War is becoming more accurate and the products needed for war are becoming more accessible, to anyone – citizen, soldier, or government. This work is a reminder of such an uncomfortable reality. And this reality isn’t an inspiration, per se, but something I feel needs to be revealed.

You can see Jilly’s work at http://jillyballistic.tumblr.com/ Her pieces are now featured in Outdoor Gallery, a standout book by Yoav Litvin, collecting pieces from several street artists. Outdoor Gallery is available at the MoMA, Guggenheim, Strand Bookstore and Zakka (BK) next week.