Read the Lone Survivor and other Movie Reviews at Manhattan Digest!

For a while, attempts by filmmakers to make movies set in the Iraq or Afghanistan wars were hindered by attempts to recreate the form and narrative of Vietnam movies, in style if not outright theme. Add the fact that audiences initially didn’t want to see in cinemas what they were getting from 24 hour news channels, early Afghan/Iraq war films were met with about as much success as John Wayne’s poorly received attempt to turn Vietnam into a World War II movie in The Green Berets. With a new arena came new rules, new soldiers, and new stories, and it wasn’t really until The Hurt Locker focused on the arena itself that the unique soldiers and stories began to engage audience and critic discussion. Now that the new rules were established and a little time for the public to come to grips with the wars, subsequent works such as the miniseries Generation Kill and Kathryn Bigelow’s follow up Zero Dark Thirty could follow actual soldiers and agents involved.

Peter Berg comes in to challenge Bigelow’s near monopoly on tales from the new arena with Lone Survivor, the true story of a failed mission against Taliban leader Ahmad Shahd by four members of Navy SEAL Team 10 in the mountains of Afghanistan. It is not Peter Berg’s first look into the area, as he previously directed The Kingdom, which flopped. Having since continued with the meager Hancock and notorious flop Battleship, he returns to the topic of the wars in the Middle East with a tighter budget and narrower focus, which ends up serving him well. So well, in fact, that Lone Survivor is turning out to be a surprise hit, having taken in nearly as much in its first weekend as The Kingdom did in its entire run, with almost half the budget.

The movie starts with a low resolution montage of Navy SEAL training rendered like an abject perversion of a military recruitment video, where minds and bodies are stretched and strained instructors and drill sergeants demands that the soldiers will themselves beyond their limits. The point of this introduction seems almost subverted by the glossier second beginning of the movie, a bookend element where Marcus Luttrell returns by helicopter broken and battered and near death. An elegiac voice over about camaraderie and brotherhood begins, and then the movie switches into a third beginning and the story actually starts.

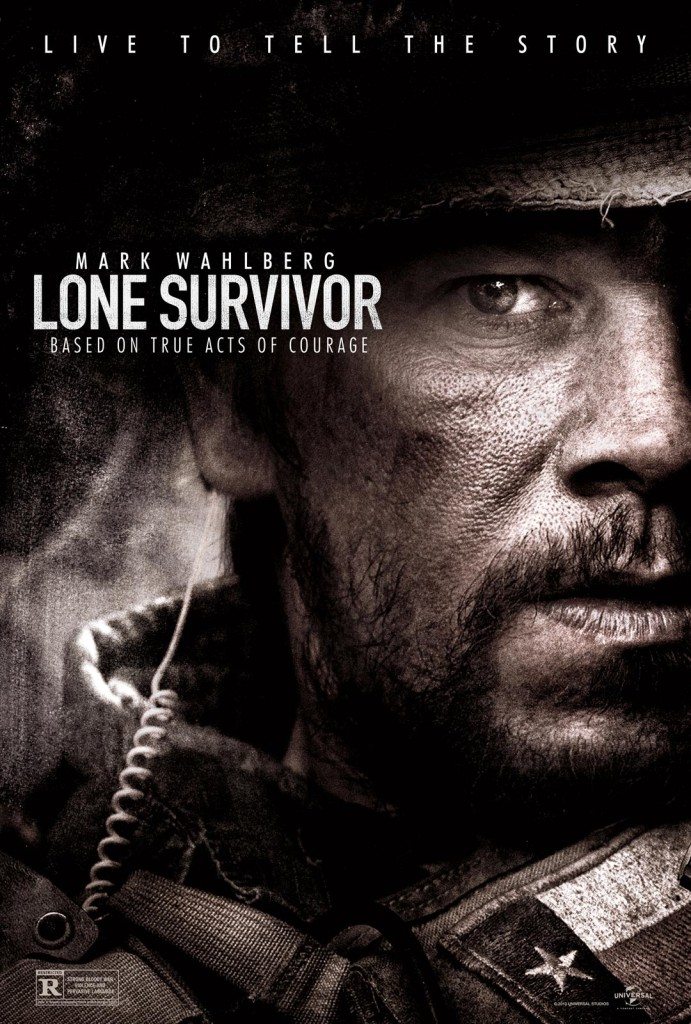

Mark Wahlberg plays Marcus Luttrell, the lone survivor and memoirist of the ill-fated Team 10 group. He’s accompanied by Taylor Kitsch, Emile Hirsch, and Ben Foster on a mission to kill Ahmad Shah, a Taliban combatant responsible for the deaths of dozens of American soldiers and the brutal execution of villagers he suspects of aiding Americans. Shah (Yousuf Asami) is laying low in a village in the mountains of Afghanistan, and it’s up to Team 10 to track him down.

First approach goes well, including visual identification of Shah. It’s everything else possible that goes wrong, in some mad mix of Murphy’s Law in the mountains. Rather than hiding with a few militants, Shah is discovered surrounded by some 200 armed men. Comms delay confirmation of their recon and eventually cut off altogether. And then a shepherding family accidentally steps across the team’s hiding place, and the entire mission is compromised.

This scene turns out to be one of the highlights of the movie. Luttrell and his men capture the family and debate whether they should compromise the mission and let them go, or kill them despite their innocence in order to keep everything under control. Their dilemma is inflated by a wary observation: if they kill the family, their faces will be plastered all over CNN as war criminals. If they let the family go, their decapitated heads will be all over Al Jazeera. This strange and semi-paranoid observation of media awareness in an otherwise clichéd morality tale. The soldiers can’t just act as warriors but also representatives.

They let the family go and know their fate is doomed. From there it only gets worse. The Taliban takes the offensive and the team goes on a desperate defensive retreat where every bit of damage they take decreases their chances of survival exponentially.

And they take a lot of damage.

Afghanistan is represented by the high desert and mountain ranges of New Mexico, using locations Berg initially seems to take unnecessarily lengthy interest in until the action explodes and it turns out the geography itself adds its own whips and cracks at the beleaguered combatants’ increasingly shredded bodies. The mountains come to be more than just a setting but an antagonist, throwing obstacles in the form of scraggly cliffs, sightline disrupting trees, and even some extra frag to aide the Taliban’s RPGs. Even the local flora and fauna seem to be against them.

Early establishing shots of high contrast and dried out rock faces are juxtaposed with quick shutter imposed jagged movement and harsh light to create a particularly biting quality to the violence. The confounding situations the soldiers seem to end up in are made even more chaotic by editing that jump cuts and even occasionally breaks the line of action (jumps to the other side of a soldier) over focus snaps and time-ramps. However, the qualities of these editing effects are held together by an impressionistic sound design.

The sound design, in fact, is one of Lone Survivor’s best aspects, recreating surges of adrenaline and moments of chaos, disorder, and confusion. Audio is helped along by an interesting score by Explosions in the Sky, a mostly fitting choice as the marching band tum-tutting quality of the drums works for the militaristic aspect while the reverbed trills and thrums of post-rock guitar bring in the anxiety.

For the most part the movie manages to make the combat so harsh that it doesn’t look entertaining or fun. Luttrell’s book, however, is a homage to the sacrifices of his brothers in combat under duress of an extreme and hard to imagine circumstance, and Berg pays tribute to it with the bookended plot voice over that seems to contrast mightily with his otherwise sharp-edged movie. Thus, at various points the movie suffers a creep of sentimentality, especially as Explosions in the Sky covers David Bowie’s “Heroes” as a dirge. However, the strange opening montage manages to tie the two seemingly conflictual representations together: Luttrell and his men managed to get as far as they did due to extraordinary levels of willfulness and physical strength.

It’s interesting to note that at various points the soldiers call each other Spartans. Lone Survivor is like an inverse 300, where a small group of raiders end up besieged in a foreign land in gritty realism and surprising humanism instead of defending their own land in a cartoonish CG fantasia.