Ten years ago, the Russell family was met with tragedy. Young siblings Tim and Kaylie were separated after Tim shot their father to stop him from mauling their mother. Tim was taken to an insane asylum and Kaylie left with their parents estate, which she used to put herself through school in pursuit of antiquities to investigate the past of this mirror that their parents bought, and which Kaylie believes to be haunted.

Well now Timbo is getting out of the looney bin and Kaylie has, with a hefty bit of foreshadowing, managed to find the mirror once again. The two return to the house, where Kaylie has set up an elaborate system of cameras and safeguards to attempt to prove, objectively, that some paranormal force is responsible for the mayhem.

From this bare bones narrative, Oculus starts to do something a little different. Kylie’s set up is almost a direct answer to every horror filmgoer’s wish that the characters try a little scientific controlled setting observation of their perceived ‘supernatural occurrences.’ She has multiple cameras set up with alarms to alert her re: battery, recording media, and food breaks, and then various alarms to remind her of the alarms; outside check-ins, inside kill-switches, and replacement parts. Meanwhile, her manic flyover of these things are met by equal measure with the recovered patient psychobabble of Tim, who attempts to explain how Kylie and he clearly must have invented their memories of any particular ghoulish influence on an otherwise very real tragedy.

But as they go about gearing down to prove or disprove the impossible, the memories of that night resurfaces in each, and the movie cuts back and forth between the mirror’s seduction of their father in the past and the psychological tricks it plays on them in the present.

Structurally, Oculus is really interesting. It has to balance moving back and forth between Kylie and Tim’s perspectives, including moments where either character is not entirely sure what they are seeing is real, while also moving between the perspectives of the elder Russells, who aren’t prepared to know whether what they’re seeing is real.

With all the perceptual shifts and the motif of the cameras, one would think Oculus would go with the found footage subgenre, but writer/director Mike Flanagan keeps it clean and focuses on balancing the two tempers of his story while building up to the ultimate crescendo.

It’s not all as clean as it could be. The cross-cutting allows some opportunities for older Kylie and Tim to separate where otherwise their separation would have to be contrived. If you watch closely, their movements through the house don’t always follow a rational path. However, the movie excuses itself by doing two other things instead: the movements of the adult siblings do follow the movements they traced as a kid, in matched action between the tragedy of the past and the boiling intensity of the present; and the younger siblings seem to be as much haunted by their elder selves as visa verse, in some cases even crossing paths within the same frame.

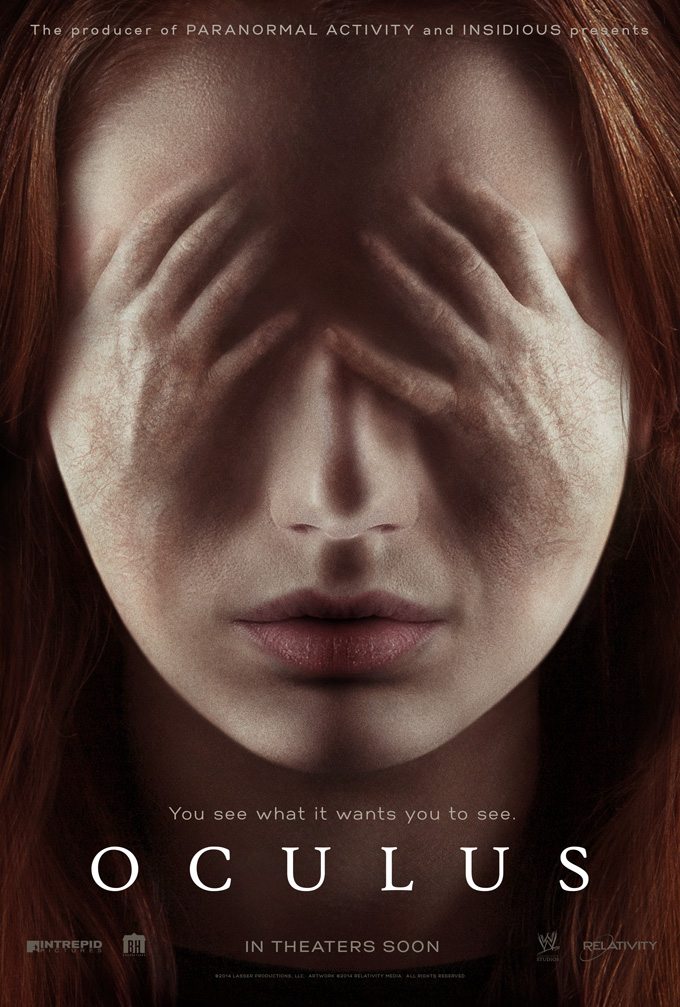

Which choreography actually is quite pleasureable to watch, if you can handle things like peeled fingernails, broken teeth, and the occasional gleam of some floating demon woman’s eyes flickering along the movement of slamming doors with disproportionate hinge:oil ratio. Oculus is a pretty standard haunted object story, and, well, centers around a mirror. Expect tilt focuses revealing shockers from dark corners and lights to be persistently unlit.

This movie features some interesting casting choices from the wide world of geek chic, mainly Karen Gillan from Doctor Who and Katee Sackhoff from Battlestar Galactica and Riddick. With the situating of the recording gack, it seems like Oculus is aiming for a higher level of film nerd, but ultimately it wraps itself neatly in stock horror and is better for it, as with all the other structural things going on, the movie could have become messy quickly.